Private versus Public Efforts Manage Risky Drugs: The Case of Accutane

Determining whether drugs and medical devices provide safe and effective treatment is critical. However, many treatment options do not fit perfectly into these categories. Instead, most choices involve comparing the relative risks of harmful side effects and potential medicinal benefits. This trade-off implies a more complex problem and warrants special consideration.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration typically does not address the trade-off problem because it faces strong incentives to avoid approving a drug with risks of harmful side effects. Approving a drug that might later result in significant harm would damage the agency’s reputation, its discretionary authority, and perhaps its command of budget dollars and other resources. Private interests, in contrast, have stronger incentives to provide potentially dangerous treatment options while devising ways to prevent avoidable risks to its customers.

The key question is, how effective are private efforts in managing these risks? An important related question is, how effective would private efforts be compared to public efforts provided by the FDA? Real-world examples providing such comparisons are highly uncommon because drugs with significant known health risks are seldom approved for use by the FDA.The case of Accutane is a rare exception, one that sheds light on the topic of comparative risk management.

Accutane’s Unique Story

In 1982, Hoffman-LaRoche’spath-breaking drug Accutane (generic name: isotretinoin)won FDA approval to treat nodular acne. Nodular acne is a painful, sometimes disfiguring form of acne that is often extremely difficult to treat. Consequently, medical journals hailed Accutane as a “miracle medicine” (Mobacken, Sundström, and Vahlquist 2014) and one of “the greatest breakthroughs in acne treatment over the last 20 years” (Meadows 2001).From 1982 to 2000, Accutane was prescribed to over 5 million patients (Doshi 2007) and remained a consistently effective treatment until it was taken off the market in 2010after it was unable to compete profitably with generics equivalents (Main 2009).

Whileunprecedently effective, Accutane had numerous side effects. The most concerning of which was its potential to harm fetal development if a female user became pregnant.

To prevent female users from becoming pregnant, Hoffman-LaRoche created, implemented, and enforced a program to educate female patients about the dangers of becoming pregnant while using Accutane and guide physicians on how to safely prescribe and distribute it.

Private Governance of Accutane

Under Hoffman-LaRoche’s program, physicians who wanted to prescribe Accutane were required to register with Hoffman-LaRoche’s prescriber tracking system. After registration, the physician received a pregnancy-prevention kit with educational materials and consent forms designed to help physicians gauge the risk of the patient not stringently following the treatment protocol. If Hoffman-LaRoche believed a physician were negligently prescribing Accutane, it could then ban the physician from prescribing it. Given Accutane’s popularity, the potential ban served as a strong financial incentive for physicians to comply.

Hoffman-LaRoche required female patients were to show a negative pregnancy test and complete and sign a ten-step consent form before beginning treatment. The form was signed by the physician to demonstrate the patient understood the risks of harm posed to the fetus if she became pregnant.

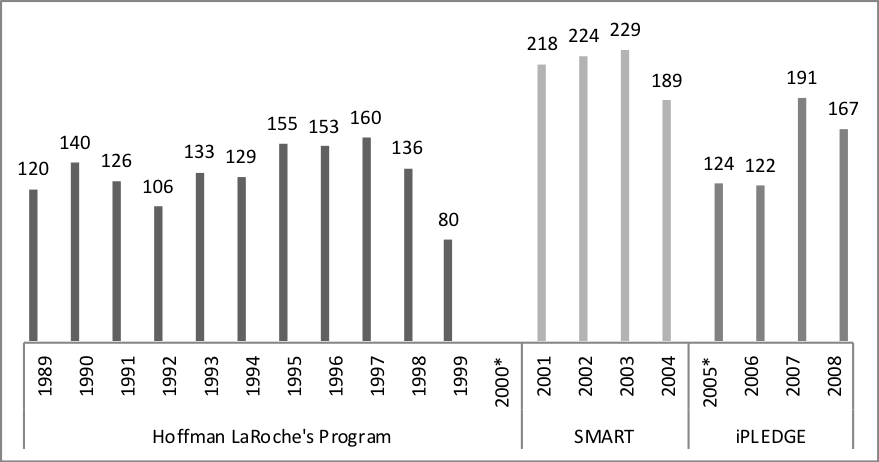

Both FDA documents and medical journals provide evidence of the program’s success. From 1989 to 1998, pregnancy rates per 1,000 female patients nearly halved,from about 4 percent to slightly above 2 percent (March 2017):

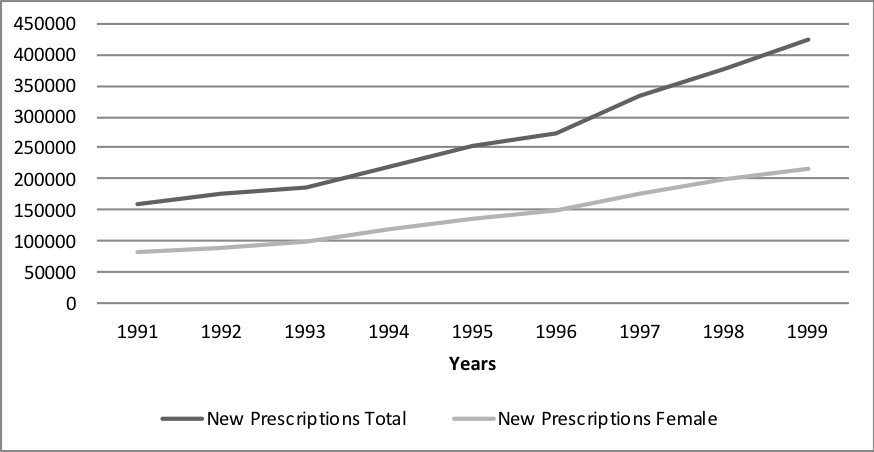

Over this period, physicians routinely denied Accutane to an estimated 15% of their patients based on the guidelines provided by Hoffman-LaRoche’s pregnancy-prevention program kit (March2017). Despite regularly denying patients access to Accutane, total prescriptions increased during largely the same period (March 2017):

Despite evidence of successfully distributing the drug while reducing pregnancies, the FDA considered the program a failure and replaced it with its program in the year 2000.

The FDA’s Evolving Effort to Manage Accutane

Stage 1

The FDA’s first attempt to manage Accutane was called the System to Manage Accutane Related Teratogenicity (“teratogenicity” is a medical term for a drug that causes birth defects) program. SMART, as it was often abbreviated, was fully implemented in 2002. Under SMART, all guidelines provided under the Hoffman-LaRoche’s program became mandatory. SMART also added more required steps before a prescription could be issued.

A physician hoping to prescribe Accutane under SMART registered with Hoffman-LaRoche to receive stickers (portraying a pregnant woman under a prohibition sign). These stickers were applied to prescriptions to indicate patients complied with all required steps. Pharmacies dispensing Accutane could only fill prescriptions that had these stickers.

Female patients were now required to produce two consecutive negative pregnancy tests and sign consent forms requiring them to use two forms of contraception from an FDA approved list before receiving a sticker-marked prescription. Patients and physicians were required to complete this process every month until treatment ended. Treatment often lasted 4 to 5 months.

Many physicians found SMART overly burdensome. Some elected to no longer prescribe it (Stashhower 2003). This worked to severely decrease the availability of a proven and effective treatment option. From 2002 to 2003, Accutane prescriptions decreased by an estimated 23% (Mendelson, Governale, Trontell, and Seligman 2005).Over the same period, the FDA reported increases in pregnancy rates[1]. Overall, the medical literature found SMART was ineffective and likely harmful (Lipper 2007; Brinker, Trontell, and Beitz 2002).

In reaction to sharp decreases in availability, patients began purchasing Accutane online. Within SMART’s first year, the FDA noted several websites where Accutane was available for purchase, “either with no prescription, with only an online questionnaire, or based on a faxed prescription” (Woodcock 2002).

In addition to harming fetal development, Accutane may have other side effects (to the liver and other organs)that would go unnoticed without oversight by a medical professional. Although the FDA’s program intended to make treatment safer, it had the opposite effect and even worked to promote more dangerous methods to take it.

Stage 2

SMART was short lived, only lasting three years. However, the FDA replaced it with a significantly more stringent program named iPLEDGE, which is still used today. There were two motives for the change. The first was the clear failure of SMART to reduce patient pregnancies. The second was Accutane’s patent expiration. To prevent generic competitors from designing programs to administer treatment, the FDA created iPLEDGE to govern Accutane and its generics. In the FDA’s own words,

“the central tenet of the isotretinoin risk-management program [iPLEDGE] is that the one centralized registry, the system of clearinghouse be created and that all prescribers, dispensing pharmacies, and patients participate in the risk management program in order to prescribe, dispense or receive the medication.”[2]

The FDA Doubles Down

iPLEDGE has been described as, “one of the most rigorous risk-management programs for therapeutic agents ever established” (Schonfeld, Amoura, and Kratochvil 2009). Under iPLEDGE, patients, physicians, and pharmacies dispensing Accutane or its generics were required to register through the government website iPLEDGE.com. Physicians are allowed to write prescriptions only to registered pharmacies.

Female patients must take monthly online exams testing their understanding of iPLEDGE’s rules and contraceptive requirements. They must also produce two negative pregnancy tests every month. The first test must be produced in the physician’s office. The second must take place in an approved lab. Once a prescription is written, the patient must have it filled within seven days. If she does not fill within the allowable period, she is“locked out” of the program and ineligible to receive a prescription for 23 days. This process is repeated each month until treatment ends.

During iPLEDGE’s first year, technical problems with iPLEDGE.com caused frequent delays in administering and completing treatment. According to a 2006 survey of 378 dermatologists registered with iPLEDGE.com, 90% faced technical difficulties that resulted in 52% of treatment plans facing delays (Boodman 2006). The same survey also found 39% of patients experienced technical problems when trying to register and complete their exams.

In addition to a poorly designed website, data from the FDA and medical literature suggests pregnancy rates did not decrease under iPLEDGE. March (2017) reports total pregnancies under each program:

Data for the year 2000 is unavailable because the FDA did not keep track of total pregnancies while transitioning to SMART. Similarly, while transitioning from SMART to iPLEDGE in 2005, the FDA only recorded pregnancies from April-December.Unfortunately, data on total prescriptions over the period is unavailable. But, by examining surveys conducted in academic medical pieces, it is apparent that pregnancy rates were not reduced under iPLEDGE.

In 2005, prescriptions for Accutane decreased by 23% (Shin et al., 2010). Generic Accutane prescriptions decreased 16%in first half of 2005 (Dooren 2006). By 2007, after many of the technical difficulties with iPLEDGE.com were addressed, Total prescriptions decreased an additional 10% (Shin et al., 2010).Some estimates conclude that iPLEDGE was no more effective than SMART, the program it was supposed to improve upon(Shin et al. 2011). When comparing total pregnancies with concurrent decreases in prescriptions, it is hard to reach a different conclusion.

Patients also continued to acquire the drugs online illegally. This became so common under iPLEDGE that the FDA sought to reduce online purchases by creating a special webpage to warn patients about the dangers of using Accutane without a physician’s guidance.[3] But why would the FDA need a special webpage to provide this information when iPLEDGE required so much patient knowledge and understanding?

The answer, according to the medical literature, was that iPLEDGE’s educational efforts were largely ineffective. According to Werner et al. (2014), “The iPLEDGE program increases anxiety about isotretinoin more than it helps women feel protected from the teratogenic risks.” However, the anxiety was not accompanied by increases in recommended contraceptive practices by patients. Pinheiro et al. (2013) examined the 24-month period before and after the implementation of iPLEDGE and found no change in the use of contraceptive practices between the periods.

Lessons from Accutane

An important prerequisite for a successful pharmaceutical market is a reliable way for determining whether or not drugs are safe and effective. A critically second step is a way to compare the potential benefits with the inherent risksthat most drugs possess. Accutane’s benefits and risks were governed privately by its manufacturer and then by the FDA. This unique history allows for a comparison between private and public efforts to manage a potentially dangerous drug, one that is uncommon in a single country.

Evidence from medical literature, physicians, and the FDA convincingly indicate private risk-management efforts under Hoffman-LaRouche were more effective in reducing patient pregnancies and providing patients access to treatment. When the FDA put itself in charge of managing Accutane and its generics,pregnancy rates increased while prescriptions sharply decreased, creating the opposite of the desired outcome.

The case of Accutane provides an example of how private interests provided a solution to a pressing healthcare problem without state involvement. While the private program was imperfect, it was better than the alternative programs provided by the FDA. Policymakers who ignore the incentive structures of alternative risk-management regimes overlook one of the most important determinants in health outcomes. At worst, they run the risk of worsening the very problems they wish to solve.

Works Cited

Boodman, S., 2006. Too hard to take. The Washington Post, 2006 September 5. [online] Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/09/03/AR2006090300590.html [Accessed July 2015].

Brinker, A., Trontell, A., and A. Beitz, 2002. Pregnancy and pregnancy rates in association with isotretinoin (Accutane). Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 47(5): 798-779.

Dooren, C., 2006. Accutane iPledge program requirements leading to illegal online sales. [online] Available at: Wall Street Journal, 13 September 2006.

Doshi, A., 2007. The cost of clear skin: balancing the social and safety costs of iPledge with the efficacy of Accutane (isotretinoin). Seton Hall Law Review, 37(2): 625-660.

Lipper, G., 2007. Isotretinoin and iPLEDGE: too much regulation or not enough? Medscape Dermatology. 12 January [online] Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/550255 [Accessed October 2015].

Main, E., 2009. Prescription acne drug pulled from shelve. Rodale News, 13 July. [online] Available at: http://www.rodalenews.com/acne-treatment-drug-accutane-pulled-market?page=0 [Accessed April 2014].

Meadows, M., 2001. The power of Accutane. FDA Consumer, 35(2): 19-23.

Mendelson, A., Governale, L., Trontell, A., and P. Seligman, 2005. Changes in isotretinoin prescribing before and after implementation of the System to Manage Accutane Related Teratogenicity (SMART) risk management program. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 14(9): 615-618.

Mobacken, H., Sundström, A., and A. Vahlquist, 2014. 30 years with isotretinoin “miracle medicine” against acne with many side effects. Lakartidningen, 111(3-4): 93-96.

March, Raymond J. “Skin in the Game: Comparing the Public and Private Regulation of Isotretinoin” Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(3): 649-672.

Pinhero, S.P., Kang, E.M., Kim, C.Y., Governale, L.A., Zhou, E.H., and T.A. Hammad, 2013. Concomitant use of isotretinoin and contraceptives before and after iPledge in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiology Drug Safety, 22(12): 1251-1257.

Schonfeld, T.L., Amoura, N.J., and C.J. Kratochvil., 2009. iPLEDGE allegiance to the pill: evaluation of year 1 of a birth defect prevention and monitoring system. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics, 37(1): 104-117.

Shin, J., Cheetham, T.C., Wong, L., Nui, F., Kass, E., Yoshinaga, M.A., Sorel, M., McCombs, J.S., and S. Sidney., 2011. The impact of the iPLEDGE program on isotretinoin fetal exposures in an integrated health care system. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 65(6): 1117-1125.

Stashhower, M., 2003. Pregnancy rates associated with isotretinoin (Accutane) and the FDA. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 49(6):1202-1203.

Werner C. A., Papic M. J., Ferris L. K., and Schwarz E. B. (2015), ‘Promoting safe use of isotretinoin by increasing contraceptive knowledge’, Journal of the American Medical Association: Dermatology, 151 (4): 389–393.

Woodcock, J., 2002. Concerns regarding Accutane (Isotretinoin). [online] Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Testimony/ucm115126.htm [Accessed April 2016].

[1] See the FDA document, “Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee Briefing Document for NDA 18–622 Accutane® (isotretinoin) Capsules” page39.

[2] See the FDA’s “Isotretinoin Update” page 7:http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4202B1_10_FDA-Tab10

[3] Seethe FDA’s “News and Events, FDA News Release: FDA Launches Web Page Warning against Buying Accutane and Its Generic Versions Online”.